We are offering a series of articles that will help shareholders in their investment decisions. In this first article, we look at how shareholders can protect themselves from aggressive financial reporting that can magnify revenues and profits and increase share values temporarily.

Many readers of the financial press will know that the truth about any company’s financial position does not necessarily correspond to the financial information being reported to shareholders. Indeed, they will have noticed what the one single reason is for many companies suddenly collapsing (sometimes literally overnight) amidst periods of high share values. This one single reason will usually be the discovery (many times accidental, and many times as a result of some diligent analyst spending late hours at work!) that although the company in question is reporting profits, in actual fact it seems not to have enough cash in the balance sheet to pay its dues on time! Following this ‘discovery’, everybody panics and all interested parties ‘take action’, with the result that the company has no other way out of the problem but to go into bankruptcy.

Though there is no one solution for the prudent shareholder to anticipate such situations, there are ways in which they can protect themselves, for example by asking the right questions. We look at these more closely below.

The main question that we will be addressing in this article is:

How is it that a company manages to report profits that do not exist?

The answer is to be found in what we call “aggressive” accounting methods. A good example of such practice is the bringing forward of revenues that relate to future periods: instead of being reported in those future periods they are reported in the current period.

Let us look at some examples of how revenue reporting can be misleading and therefore what kinds of questions shareholders, or their advisors, should be asking.

Let’s go back to basics for a moment and ask the question:

When is a sale or the service to a client complete?

This is an important question because it is at the point when the sale is complete that the revenue which relates to this sale or service can be shown in the financial statements; or as we say in Accounting, it can be reported, or even more formally, it can be “recognised”. It does not matter when the cash is actually received, as long as it is probable that cash will be received. What matters for recognition of revenue is that it relates to the period that it is “earned” and this is simply the period that the customer is enjoying our product or service.

However, life is not always as simple as having a product shipped to a customer, who then receives it, after which the sale is deemed complete. Take as an example a customer that we have agreed with to pay us the value of the sale – 2 million euro in instalments over a period of 5 years. We can go on and recognise the whole sale of 2 million in the year of sale i.e. year-1, but what if the customer goes out of business in year-3 and does not pay the remaining instalments amounting to 0.6 million? All this income that was recognised in year-1 but now cannot be paid to us, must now be reversed in year-3 or, as we say in Accounting, restated. In other words in year-3 we must show a loss of 0.6 million to ‘reverse’ the income we ‘recognised’ in year-1. However in year-1 we had shown income that was not ‘earned’ and we have misled the readers of the financial statements into thinking that our operations were more profitable than in reality. And the value of the shares went up! Such restatements can be catastrophic to shareholders as they will sooner or later see their share values falling from the sky above!

Before we move on to more examples of whether accounting methods show a reasonable picture of earnings, we need to ask another basic question, that is:

What constitutes revenue?

Consider as an example a car dealer who sells a car for 56.000 euro and receives as commission 4.000 euro. What is then the car dealer’s revenue? Is it 56.000 euro or just 4.000 euro? The car dealer may be happy just to show in the financial statements the net amount as revenue but a car company that needs to show to prospective investors strong growth in revenues will want to report the 56.000 euro as income and the 52.000 euro as cost. In most cases the “strength” of a company is judged by the size of its revenue i.e., income before deducting costs. What is more, many companies want to show increase in revenue over the years to show growth.

Consider another company that buys cameras from a supplier and sells to a customer at a margin. The full price paid by the customer will be shown as revenue and the price paid to the supplier will be shown as cost. However, in many situations the company may arrange for the delivery to its customers to be effected directly from its supplier to its customer thus making the transaction more efficient and cost effective. In such a case, can the company still show the full price to its customers as revenue, or only the margin? Would it be fair to this company that the revenue figures are just the margin of 4,000 euro and as such show a weak position relative to a competitor for example? The only difference in the two scenarios above is simply that the logistics are more efficiently organised in sending the cameras directly from the supplier to the customer. It is hardly fair that the company should be penalised for being efficient!

Another popular and recurring phenomenon is for companies to record revenue at the point when they enter into a contract of sale instead of spreading the revenue over the lifetime of that contract. Although the revenue is not reduced over the whole lifetime of the contract, it is reduced in the financial period which is reported. “Counting the chicks before they hatch” has led many companies to restate their revenue and hence reduce profits massively, thus leading to a fall in the shares. The ultimate losers in such a situation are, of course, the shareholders.

Should we analyse revenue?

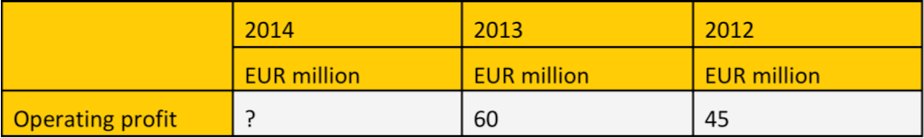

Let us look at one final example of how reported net revenue growth may mislead shareholders. Suppose the reported operating net revenue for a company is as follows:

How much would you anticipate as the likely profit for 2014 (ignoring any other factors)? You are an advisor to a client that is considering ways to invest. Does this company look promising and therefore worth investing in? You would probably expect profits to increase! The management seem to be doing a good job as they successfully increased profits from 45 million in 2012 to 60 million in 2013. So perhaps you should go on and invest in the shares of this business!

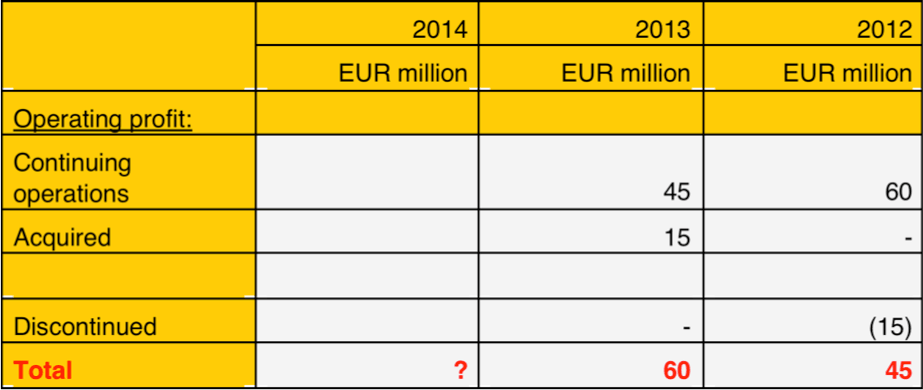

But let us first ask management a few questions and try to obtain some more information before we make the final decision to invest. Based on this new information the above numbers are now analysed as follows.

Now we see that in 2012 the basic operations that are still going on in 2013, and are expected to continue in 2014, made a profit of 60 million and not 45 million. The operations which the directors decided to discontinue in 2013 made a loss of 15 million in 2012. But in 2013 the basic ongoing operations made a profit of only 45 and not 60, i.e. a reduction in profitability by 25%. In 2014, these basic operations will probably do even worse! The newly acquired business in 2013 made a profit of 15 million but this does not reflect the strength of the core operations! This profit is after all the efforts of the previous management!

Total profits are showing growth only because the directors are able to find profitable businesses to acquire and to replace other profitable businesses that they turned into loss-making operations only to sell them again! Looking only at financial statements without additional information could be very misleading to the readers because, at first read, they would see that profits increased from 45 million to 60 million. The new additional information suggests that these directors are not really doing very well. It suggests that there is in fact a risk that they may turn any good profitable business they acquire into a loss making operation!

Do not just read the numbers. Ask questions to see if numbers can be supported!

Shareholders are not expected to be experts in analysing financial statements but surely they are able to ask relevant questions and obtain a basic understanding of the numbers that are being reported. They will then be able to consult their appointed representatives and make profitable decisions. We live in times of frequent accounting scandals. A simple restatement of revenues could mean disaster for shareholders. And this has happened too often in recent history.

Companies most likely to be “itching” for aggressive reporting are the following:

- High growth companies, for whom slow growth is inevitable, but whose management are pressurised to show continued growth.

- Companies that are popular and under constant scrutiny of the business and daily press. Even small problems attract public attention, and management are pressurised to manipulate the numbers.

- Companies in new industries engaging in new types of transactions that were previously unknown. Standards will probably be silent on such transactions and so management will be able to report numbers as per their own judgement.

- Companies with complex ownership and financial structure can make transactions less transparent, giving rise to related party transactions and conflicts of interest.

So, shareholders be warned and be reminded of the questions you need to ask!

- How is revenue defined?

- When is revenue recognised?

- Do the above constitute a reasonable measure of the revenue in the reported period?

- Are the above consistent with revenue measures employed by competitors (both domestically and abroad)?

- Are the above clearly mentioned and explained in the notes to the Financial Statements?

- If revenue is measured in an unusual way, is this reasonable, is it disclosed in the notes to the financial statements and is it justifiable in relation to risk taken?

Such ‘aggressive’ practices as we described here are becoming frequent and they are a nightmare to shareholders and the investment managers that advise them. Such practices may not necessarily be illegal but they are definitely not proper and shareholders (or their representatives) need to be aware of them. Either the economic environment or personal financial incentives for management may exert pressure to report growth in revenues as per market expectations.

International Financial Reporting Standards require judgement!

The ability to “create” the numbers that management wish to report is possible because reporting under IFRS requires judgement on many occasions, in deciding how and what numbers are to be reported. At the same time, IFRS tries to come up with standards that will prevent such “creative” reporting. So for example, IAS 18 tries to regulate the timing of recognising revenue and thus prevent the bringing forward of future revenue.

However, there is a constant battle and on-going development of new standards that are trying to address new “ideas”. The victims of such aggressive reporting are usually the shareholders who find themselves caught in the middle of aggressive reporting and a constant development of accounting standards that are becoming more difficult to understand and to interpret. Although shareholders are not expected to be experts in Accounting, they (or their representatives) should have enough financial literacy to be able to have enough understanding of basic financial statements and reporting issues so as to know the right key questions to ask in order to ensure their interests.

Revenue is one of the many traps that shareholders can fall into and a very important element of profitability. In the next article we will look at another other side of profitability: costs, and how these can be manipulated to show profits that do not exist!