We continue our series of articles meant to help shareholders in their investment decisions.

In this third article, we look at the Balance Sheet, how assets are valued, as well as how this valuation impacts the company’s shares.

The financial position of companies, at any point in time is shown in what we call a Balance Sheet or indeed, as it is nowadays called, the Statement of Financial Position. In its basic form a balance sheet shows, on the one hand, all the assets of the firm, and on the other hand, how these assets are represented by the various liabilities the firm has committed itself to or, if you like, how these assets were financed.

If you think of a newly created business that needs to be able to acquire assets, which are needed for the generation of income, buildings, a plant, equipment, furniture, vehicles, stock of goods to resell, raw materials etc. it must mobilise borrowings from various sources. So, for example, the owners will contribute capital, the banks may extend loans, the public may buy bonds, the suppliers will extend credit etc. The assets will be worked on and used up while generating income, which will be used to repay the liabilities and the corresponding reward to these liabilities: for example, dividend to the owners, interest to the banks, interest to bond holders, slightly higher prices to the suppliers for their patience in waiting to be paid, and so on.

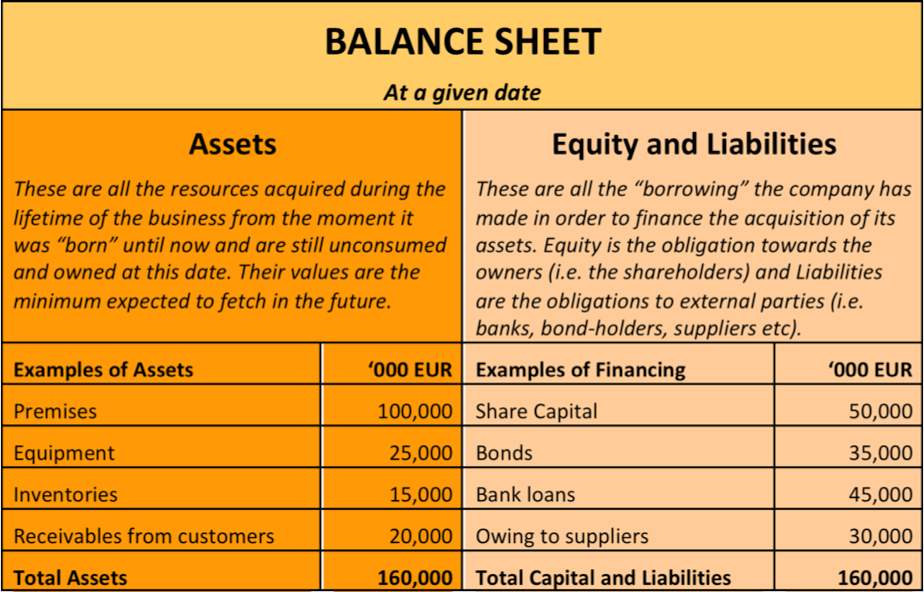

Hoping a diagram will help us visualise this, here is a very simple Balance Sheet, which like any Balance Sheet basically shows two things, i.e. the assets at a point in time and the corresponding obligations at that point in time.

We will be looking at the asset side of the balance sheet to try to understand how the value of these assets can sometimes be manipulated to give the impression that their value is high enough to “pay back” those who contributed to the business.

Every prospective investor in a company will want to look up the balance sheet to see what assets there are and if the lenders that had financed these assets will be repaid with a return. This is why it is important to know how to read it.

What are balance sheets for?

Before we see some real life examples of asset “over-valuation” let us ask the question: How come a balance sheet is at all needed and indeed why do we need to have assets and liabilities reported? Well, think of any project that has a certain lifetime. To find out if the project is successful, all we really need is to look at the total amount of cash that this project generated during its lifetime and compare it to the amount of cash that went into this project. The difference will be the profit or loss that the project has generated.

However, before the end of most projects (indeed, Coca Cola, McDonalds, Walt Disney etc. seem to have no end!) shareholders and other stakeholders need to know the financial position and financial “health” of a firm in order to help them with their day-to-day decision-making (“shall I keep my shares in this firm or shall I divert to other firms in the same industry, or different industries, or shall I purchase more shares……”) The life of projects is therefore divided into financial years (even financial quarters!) and management report at points of time. However, at these points in time buildings, plants, equipment, vehicles and other assets are still being used and therefore we need to “value” these unused assets (i.e., assets which are still used and thus still valuable) and show them in the balance sheet.

Therefore, an asset either has a current or intrinsic value, for example cash, or it can be used to generate future revenues, like for example a plant that will be used to produce products to be sold in the future. Irrespective of how much an asset was bought for or how much it cost to construct it, its value in the balance sheet cannot be higher than the reasonably expected future revenues it will bring to the firm. In other words, when an asset is listed in a balance sheet, what is communicated to the balance sheet’s readers is that this asset will bring in revenues of at least the amount shown therein. If, say, we are reporting in the balance sheet the asset receivables, then we are implying that the amount shown (in the example in the table above this amount is 20,000,000) is expected to be received in a reasonable amount of time. However this stream of “expected” future revenues has to be estimated! For example, some of our customers will not be able to pay us for one reason or another. It is here that we run into traps because judgement is required.

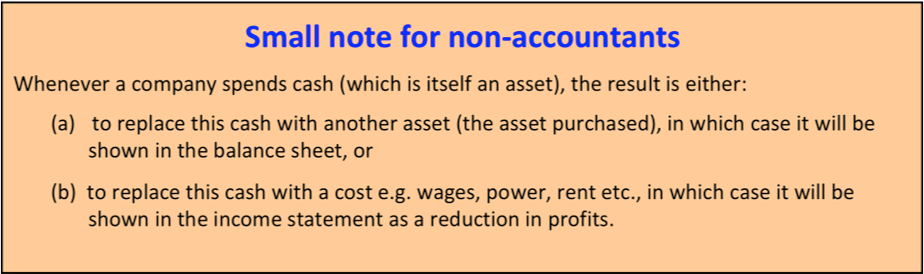

So we see that there could be an incentive sometimes to try to show spending of cash as “asset” in the balance sheet, instead of showing this spending as a cost that reduces profits (or even shows losses!). If that happens, then effectively we are overstating the value of assets in the balance sheet and, of course, reducing the value of costs in the income statement, thus increasing (should we say overstating?) reported profits. When an asset loses value, this loss in value should be shown as a “cost” in the income statement; this cost reduces profits, and hence potential dividends. Lower dividends means lower share price. Lower share price signals to the prospective investors (and to the market at large) to stay away from this company!

To complicate things a little, assets are generally carried in the balance sheet at cost less amortisation or depreciation. Let us explain this in some detail. If a firm spends say 100 million Euro to acquire an asset and expects this asset to be in use for say 10 years, it will not be reasonable and definitely not informative to the readers of the financial statements, to show the whole of the 100 million as a cost in the year of acquisition of this asset i.e. in its first year of use. It would make a lot of sense to “spread” this cost of 100 million over the useful life of 10 years of the asset in order to match this 100 million cost against each year’s benefits that this asset generates.

In other words, IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) require us to match the cost of the asset against the revenue it generates in that particular financial year – this is the Matching Concept at work. To determine the “cost” of the asset, one more thing is required and that is the residual value of the asset at the end of its useful life. If, say, the asset we mentioned is expected to have a residual value of 20 million at the end of the 10th year then we will have to spread the 100 – 20 = 80 million over the 10 years. So each year we will be showing as cost in the Income Statement 80/10= 8 million, and this will be the depreciation of the asset.

So where is the trap? To apply the matching concept and satisfy IFRS the management of the firm has to estimate the useful life of the asset as well as the residual value. This requires judgement, and as we know from our previous article, this is also where traps appear.

Beware the trap!

Let us leave theory for a while and look at some real life examples where shareholders could have avoided traps if they looked at the financial statements carefully and asked the right questions.

Example 1 – Overstating Receivables

A company in the late 90s was aggressively conducting a campaign selling fertilisers to farmers. The sales transactions were effected without any careful creditworthiness check or any strong guarantees. Over the next two years the trade receivables amounted to half a year of sales. When management changed in the third year and the new management tried to collect these receivables it turned out that nearly 50% of these receivables had to be written off i.e., to be shown as losses, thus reducing revenue and, of course, dividends. So for three years the company was reporting an asset, Receivables, which in fact had half the value shown in the balance sheet.

However, no one asked whether the debtors were able to pay their debts, no one looked at the history to ask why it was that these debtors delayed payment, and probably no one looked at the liquidity of the company to sound the alarm to chase the debtors for payments. The result was that the old management were rewarded for their bad management (they were reporting profits and receiving bonuses!) and the new management had to deal with falling share values and unhappy shareholders.

Example 2 – Overpriced Goodwill

Here we will look at an interesting asset, namely Goodwill. This is an intangible, unlike for example a plant, buildings, furniture, which are all tangible, i.e., physically visible. Goodwill arises when a company is bought at a price higher than the values of the shares as shown in the balance sheet and it relates to the good name or reputation or uniqueness of the company. It is therefore an asset like any other, as it is expected to generate future cash flows.

A certain company had purchased a leading regional newspaper in south Nameland (a country in the North of Europe), when the newspaper market was “hot”. As a result of this purchase, the acquirer recognised in the consolidated balance sheet significant amounts of assets in terms of brands and goodwill. However, due to the development of the Internet and fierce competition between newspaper publishers, this business was not able to generate profits in the subsequent years. In other words, it became apparent that the values of the brands and the goodwill were were purchased at too high a value. In recent consolidated financial statements of the acquirer, these assets were presented at their initial values less depreciation. However, if impairment analysis was carried out (to examine the value of the assets and to what extent they should be adjusted), then significant amounts of these assets would have been written off as a result of changed market conditions and the reduced ability of these assets to generate cash. Instead, many investors were trapped and spent too much investing in shares that were over-valued.

So, do not assume assets are reported transparently! Questions to be asked, therefore, are:

- Do values of tangible and intangible assets reflect real values or changes in values in the current period? Is any depreciation or write-down of value as shown in the financial statements reasonable or should more be shown?

- Are any value adjustments made fully disclosed and adequately explained in the notes of the financial statements?

- Is the accounting treatment consistent with competitors in Nameland and abroad? If not, are the differences justified and fully explained?

These are some questions that can go some way towards protecting prudent shareholders from the many different “judgement” calls that companies reporting under IFRS have to make. We have previously talked about how to identify (and beware of) “aggressive reporting” and how the matching concept under IFRS can help us get the full picture about the estimated cost of corresponding revenue, even if that cost is uncertain.

Hoping that you are finding these articles enjoyable and useful, we will come back in the next one with a discussion on derivatives! They sound complex and not for the layman but we disagree! They are easy to understand and difficult to control if we lack the basic understanding. We definitely cannot ignore them, so we will go straight into discussing them in some detail.

If you liked this article, please consider following GnosisLearning for more top quality IFRS analysis. We are also on Twitter and Facebook. Coming soon: our very own website!